The origin of the term “Generation X” is still a bit murky. We know that Douglas Coupland popularized it with his 1991 collection of short stories. But where did he get it from?

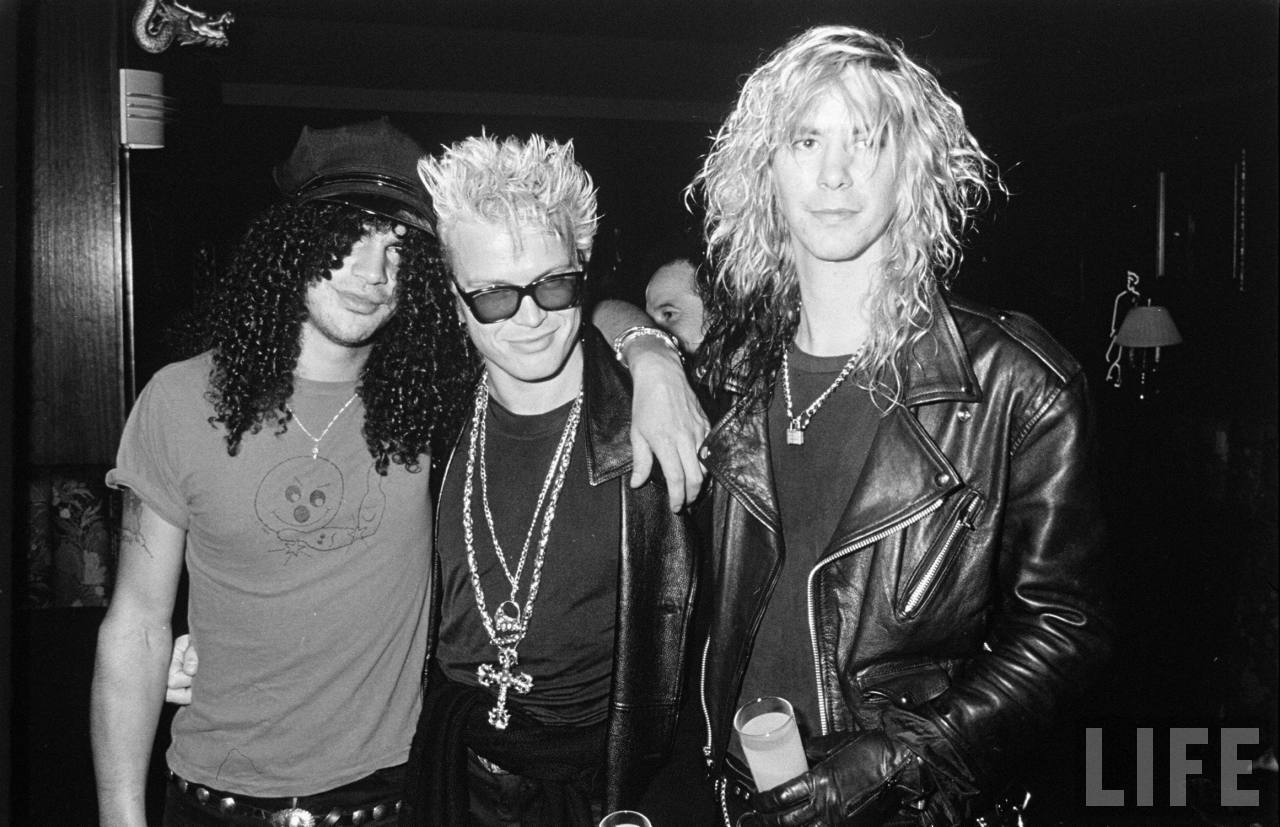

Did he graft it from the name of Billy Idol’s original punk band, which was truncated after only a few years to simply “Gen X” when they rebranded as New Romantics? This was a popular theory for some time, and while some of Idol’s lyrical content did touch on vaguely X-ish themes, Coupland has long dispelled rumors of a connection between himself and the English rocker.

Billy Idol and Slash

The term “Generation X” was first used in 1953 by famed Hungarian war photographer Robert Capa in reference to a group of young people who came of age directly following World War II.

Capa was working on a series of articles for Holiday Magazine titled Youth and the World. The series constituted a new type of experimental ethnography – the magazine talked to 23 individuals from all over the world about their lives to see if they could discover a common thread in terms of their values and outlook. Given that their adolescence was defined almost solely by the horrors of war, theirs was an experience filled with pessimism and trauma.

Editors of Holiday Magazine said of the interview subjects:

“Only one person out of twenty looks back to the past with anything like longing. For most of them the immediate past – the events of their lifetimes – has been too harsh and too cruel to remember with pleasure. And the long past – the heavy, deadening hand of history – is still the great enemy.”

Capa called them “X” because the magazine’s overly ambitious attempt to find a common theme amongst these randomly picked individuals from various countries (including Syria, Japan, Germany and others) came up short. They couldn’t identify any shared purpose, perspective or set of values between their subjects. Save for one: they all expressed support for greater individual and human rights, and they were all looking to the future for a better life.

12 years later and another team of journalists took up the Generation X moniker in a similar fashion:

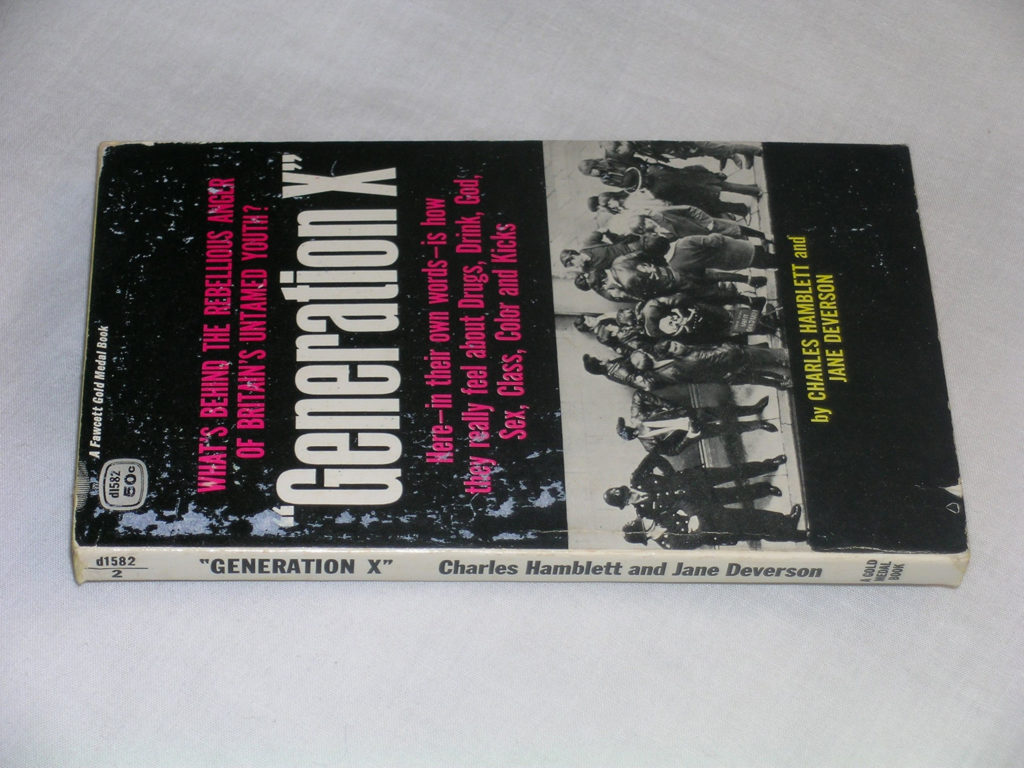

Journalist Jane Daverson was originally tasked by the editors of Women’s Own magazine to write a “nice feature on wonderful British teens and why we should be so proud of them.” But after talking to a few of these nice British teens, Daverson ditched the premise and waded knee-deep into the debauchery of the swinging sixties, telling lurid tales of pre-marital sex, atheism and rebellion.

Women’s Own refused to publish Daverson’s interviews, so instead she put together her own book on “Generation X” this time with the focus being on British subcultures of the day. Similar to Holiday Magazine, Daverson’s book profiled a cross-section of youths, interviewing them in great detail about anything they wanted to talk about, but mostly they just wanted to talk about sex, drugs and violence.

“Generation X” by Charles Hamblett and Jane Deverson

While both of these books provide fascinating examples of early youth ethnography, neither of them were the inspiration for Coupland. It was actually a much lesser known source that inspired our current understanding of Generation X.

Coupland took the term from the final chapter of a semi-satirical book published in 1983 called “Class: A Guide Through the American Status System” by the American cultural and literary historian Paul Fussell. In his book, Fussell argued that America had a British-style class system, only it was generally invisible and based on taste, rather than money. One of the classes that Fussell identified and defined was called “Category X”. Or, X-ers, for short.

X-ers were essentially modern Bohemians, or proto-hipsters, who flocked to big cities looking for art and work that required creativity. They didn’t care much for authority or advertising, and preferred no-name liquor and brandless clothing.

To quote Fussell on Category X’s fashion philosophy: “When an X person, male or female, meets a member of an identifiable class, the costume, no matter what it is, conveys the message: I am freer and less terrified than you are.”

While all these different iterations of “Generation X” seem to orbit the same tonal stratosphere, it’s in Fussell’s version that we can see the genesis of the trademark Gen X attitude. He described X-ers as a group of people that were a “self-selecting aristocracy of the talented and clever”. And if ever there was a idealized version of what Gen X was supposed to be, or aspired to be, that was it.

To find out more about everything X-related, check out our GEN X: Youth Never gets Old report from Slideshare.